Trump’s Bad Trade ‘Deal’ With China Takes Shape

by D.J. McGuire

One of the more maddening defenses of Trump’s protectionism is the insistence that his tariffs and trade wars are “temporary.” Give him the chance, his defenders say, and he’ll get “better deals” that remove tariffs all around.

This week’s Bloombergrevelation about trade talks with the Chinese Communist Party completely destroyed that argument.

China is considering a U.S. request to shift some tariffs on key agricultural goods to other products so the Trump administration can sell any eventual trade deal as a win for farmers ahead of the 2020 election, people familiar with the situation said.

The step would involve China moving retaliatory duties it imposed startinglast July on $50 billion worth of U.S. goods to non-agricultural imports, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the discussions were private. The shift is because the U.S. doesn’t intend to lift its own duties on $50 billion of Chinese imports even if an agreement to resolve the trade war between the two nations is reached, one the people said.

Let’s examine the full implications of this nonsense. First, it’s abundantly clear that Trump has no interest in ever removing the tariffs he has imposed. This should surprise no one. Donald Trump was President of the United States for less than an hourwhen, in his own inaugural, he insisted, “Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.” Within fifteen months, he had cleared out the bureaucratic resistance to his dangerous impulse and the tariff spree began. The idea that he would ever get rid of them was foolhardy.

The repercussions of this are now beginning to be seen, in geopolitics as much as economics. The Administration that touted itself as being able and willing to “stand up” to Beijing has been reduced to begging the CCP to switch its tariffs to less visible products.

Meanwhile, the regime gets a free pass on threatening Taiwan, strong-arming its neighbors in the South China Sea, using Kim Jong-un as a foil, and persecuting hundreds of thousands of Uighur Muslims in occupied East Turkestan.

The president who as a candidate railed against the rest of the world “laughing at us” is only spared hearing side-splitting gales from Zhongnanhai due to the distance of the Pacific Ocean.

The rest of the world is taking notice and will act accordingly. Those hoping for removal of tariffs now must accept the fact that they’re not going anywhere. The world will be a poorer place, with higher prices and lower production across countries and sectors worldwide.

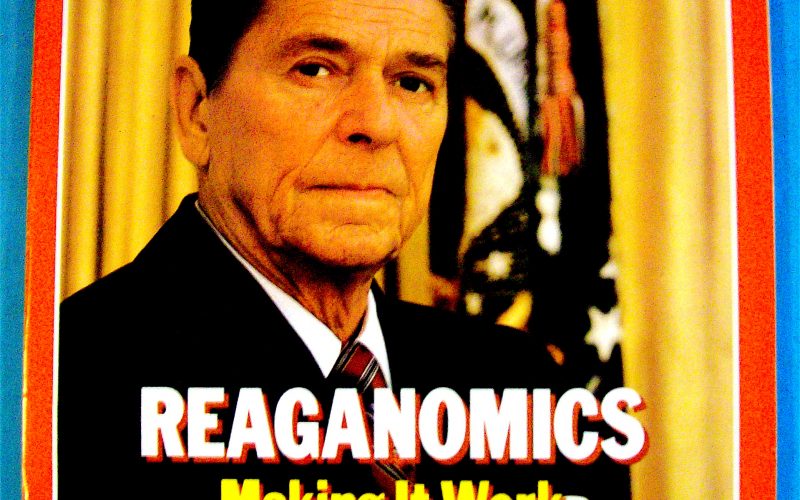

Economically, America has been shielded by timing: we’re in the late stages of a long economic recovery temporarily buttressed by a Keynesian sugar high disguised as a “supply-side” tax cut. That can’t last forever. The economic reckoning will be painful. The geopolitical effects will as well.

The one silver lining is this: no one can credibly claim Trump’s endgame is about reducing or eliminating tariffs. Anyone who still tries peddling that nonsense is gaslighting everyone in the conversation, themselves included.

D.J. McGuire – a self-described progressive conservative – has been part of the More Perfect Union Podcast since 2015. He is also a contributor to Bearing Drift.